Route Planning

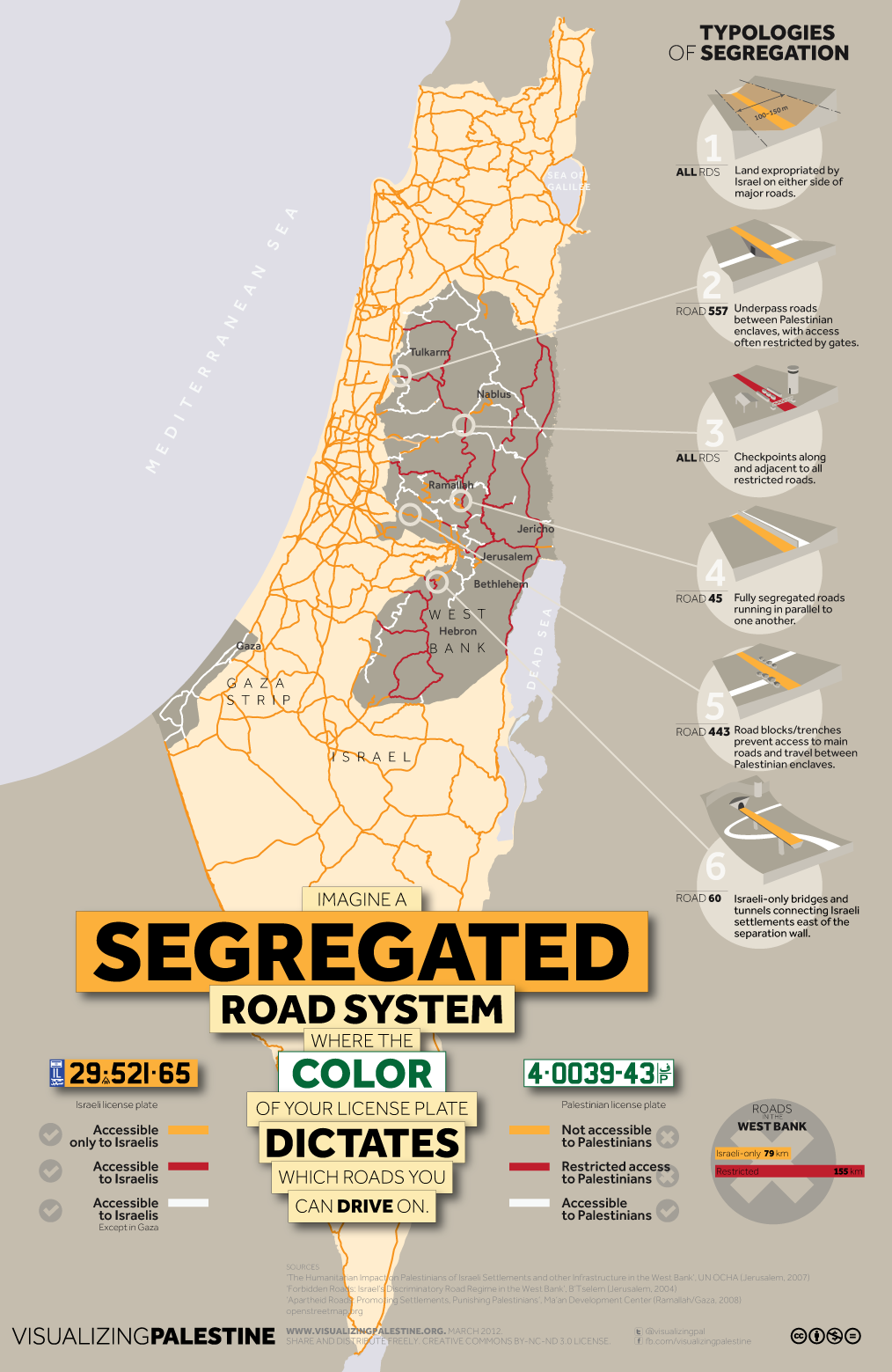

The territorial fragmentation of the West Bank is exacerbated by the divided road system, which places restrictions on Palestinian movement. 79 kilometres of so-called 'sterile' roads are only accessible to blue ID holders (Israeli citizens with yellow car license plates) and cannot be used by West Bank Palestinians (with green IDs). Palestinian presence on these roads, which usually connect Israeli settlements, is illegal. The roads designated for Palestinian use are often sub-standard non-paved or dirt tracks, which are sectioned off from the Israeli roads with high fences and can be closed without prior warning by Israeli forces. The consequences for Palestinians accessing Israeli-only roads include arrest, delays, detainment, confiscation of cars, and even death. 155 kilometres of road have restricted access for West Bank Palestinians, and often require special permits that are very difficult to obtain. B’Tselem and Ma’an Development Center provide lists of the location and length of these ‘sterile’ roads, partially prohibited and restricted roads (B’Tselem 2004; Ma’an 2008).

These restrictions are further exacerbated by the maltreatment Palestinians receive at checkpoints. The map below outlines the various movement restrictions for Palestinians on foot and in vehicles, imposed via checkpoints. On roads shared by Israelis and Palestinians, it is common for Palestinian cars, which are easily identified by their green licence plates, to be delayed and searched frequently (B’Tselem 2004; Ma’an 2008).

There are potentially severe consequences for West Bank Palestinians who attempt to pass through checkpoints into Israel or Israeli settlements within the West Bank. Therefore, the need for accurate mapping and route planning services is immense. The movement restrictions on Palestinians can have life-threatening consequences: West Bank Palestinians have died at checkpoints after being denied passage by Israeli authorities (B’Tselem 2004). Palestinians have also died at settlement entrances and bus stops after being shot by Israeli soldiers under the pretext that they allegedly posed a threat (Brown 2014).

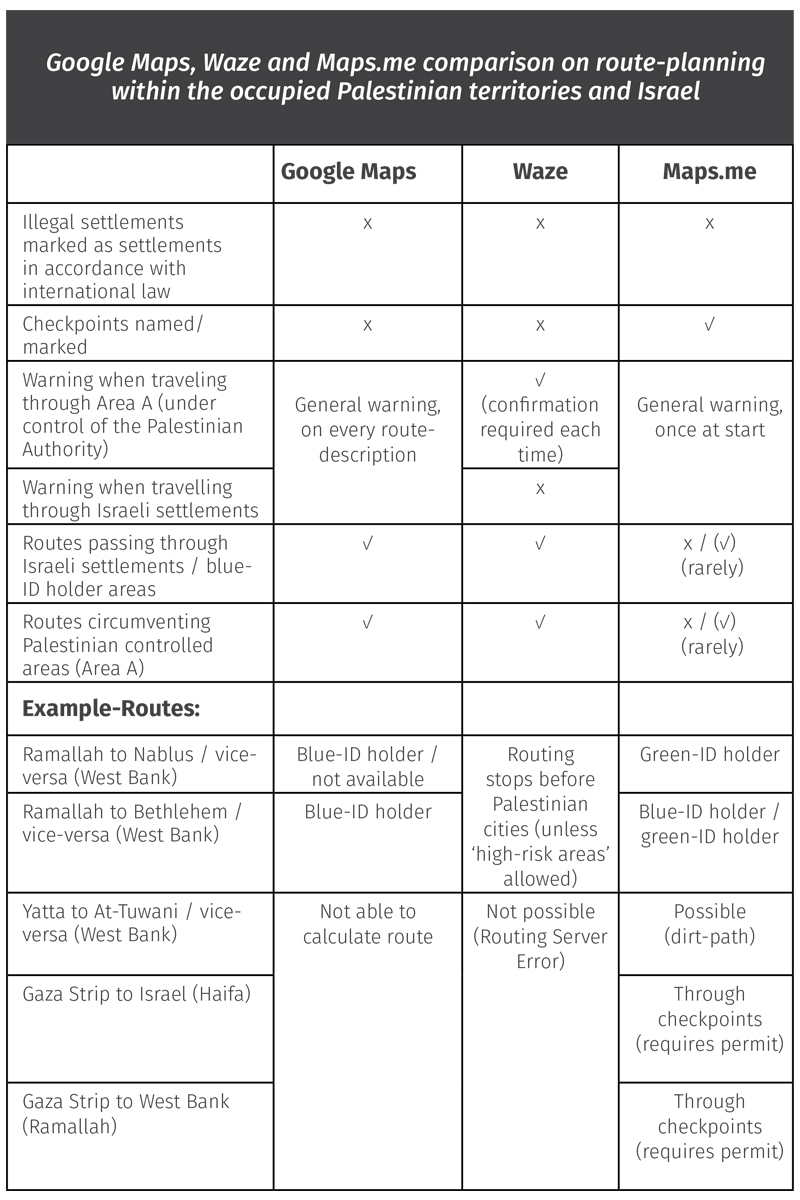

This section explains and compares the route planning applications Google Maps, Waze and Maps.me, including how these apps name checkpoints and Israeli settlements. The section also provides an analysis of route planning with the following five routes: (1) from the central West Bank city of Ramallah to the northern West Bank city of Nablus, (2) from Ramallah to the southern West Bank city of Bethlehem, (3) within the south Hebron Hills rural communities in the West Bank: from the town of Yatta to the village of At-Tuwani, (4) from Gaza to Haifa within Israel, and (5) from Gaza to Ramallah in the West Bank.

Image: Israel’s System of Segregated Roads in the Occupied Palestinian Territories - Visualizing Palestine, May 2012

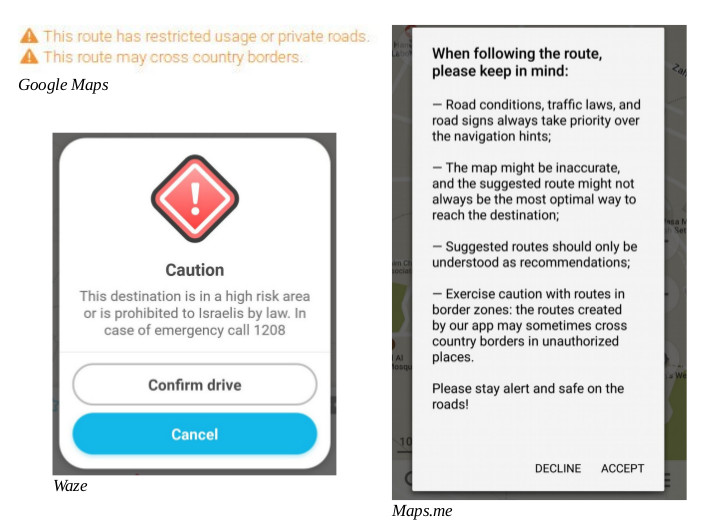

Google Maps

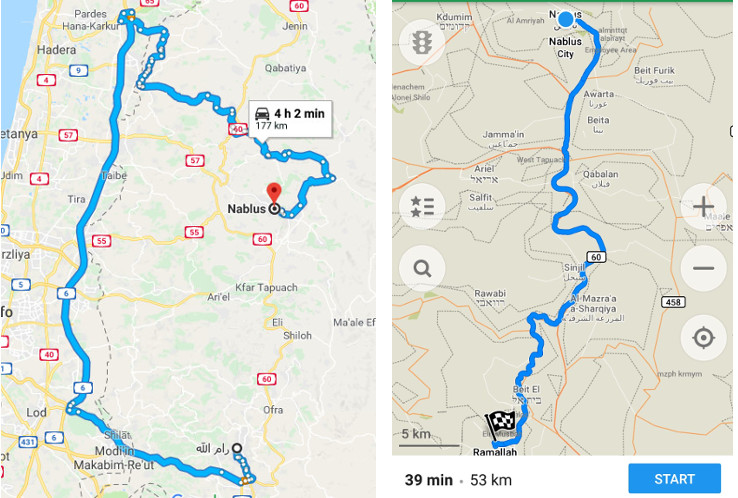

On routes within the West Bank, Google Maps prioritizes directing users through Israel rather than through the West Bank, even if this adds considerable distance to the journey. The drive from Ramallah to Nablus through the West Bank usually takes 45 minutes, however when using Google Maps, the journey takes a long route through Israel and takes 4.5 hours. In contrast, the shortest route from Ramallah to Bethlehem takes the driver through Jerusalem, which is inaccessible for Palestinian West Bank ID holders. Whenever a route passes through the West Bank, Google Maps shows two warnings on the route description: “This route has restricted usage or private roads” and “This route may cross country borders” and fails to highlight Israeli settlements or checkpoints. Google Maps is unable to calculate routes within Palestinian rural communities, or to and from Gaza, displaying the message “Sorry, we could not calculate driving/walking directions from x to y”. The app offers the option to “add a missing place” and edit information, but this “might take some time to show up on the map” as they must be reviewed first.

Maps.me

While Maps.me does not mark Israeli settlements, it does have special markers for checkpoints, which are marked as “checkpoints” with names such as “Israeli occupation border_control” or by number, for example “Checkpoint 56”. However, routing goes through checkpoints without clarifying the movement restrictions for Palestinian green ID holders. When using Maps.me for the first time, a long general warning is displayed. All routes within the West Bank and from Gaza to Israel or the West Bank can be calculated. Generally, routes between Palestinian cities within the West Bank take the driver through the West Bank, with the exception of Ramallah to Bethlehem, which is routed through Jerusalem. In the rural communities in the South Hebron Hills, Maps.me displays a small dirt road that is used by the Palestinian population in this area instead of the settler highway. Thus, Maps.me is generally usable for Palestinian West Bank green ID holders. It also offers logged-in users the option to add and edit locations based on the open-source OpenStreet Map.

Waze

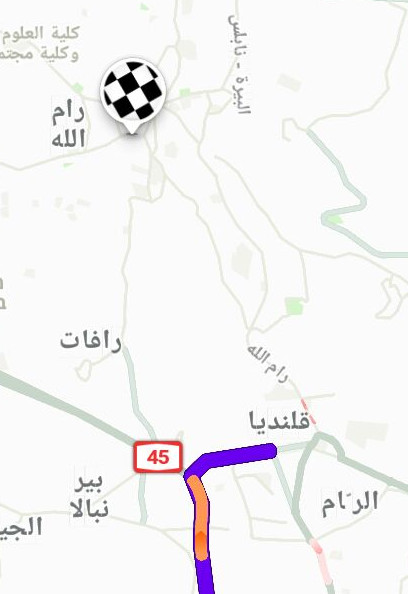

Waze is an Israeli-developed app (Waze 2014) that is now owned by Google. The app works within Israel and Area C, and includes warnings about traffic, accidents and police controls. All directions given are exclusively within Area C and thus stop before entering major Palestinian cities. For instance, when indicating a route to Ramallah, located in Area A, the directions will abruptly stop at the checkpoint in Qalandiya. Only when the option to “avoid high-risk areas” is switched off is it possible to plan routes that reach Palestinian cities. When searching for Palestinian locations such as Bethlehem, primary suggestions with the same name are all located inside Israel, and the Palestinian city of Bethlehem is located further down the list. Before calculating routes within “high-risk areas” – Palestinian areas – Waze displays a warning, including the number to call in case of emergencies, and requires a user confirmation to start the route planning. Routes in rural Palestinian areas and to or from Gaza are not possible, and instead an error message is displayed. Waze has an “active community of online map editors who ensure that the data in their areas is as up-to-date as possible” and offers logged-in users the option to “edit the map” and add places and infrastructure such as roads (Waze n.y., Waze Support 2018).

Screenshot: Google Maps vs. Maps.me routing Ramallah - Nablus

Screenshot: Route-planning to Ramallah - Waze

Comparison

None of the three route-planning apps analysed mark Israeli settlements as being illegal in accordance with Art. 49 IV Geneva Convention and Art. 55 of the Hague Regulations. Maps.me is the only service that marks checkpoints on its maps, but it does not take them into consideration when planning routes and navigating users. All three services display a warning, different in length and specification concerning borders and accuracy of the route. Waze specifically warns when entering a Palestinian area as a “high risk area” and requires a confirmation to begin the route planning. All three mapping apps fail to take into account the movement restrictions and repercussions for Palestinians when planning routes. The clearest example of this is the route between Bethlehem and Ramallah. Google Maps takes the fastest route, which goes straight through Jerusalem, thus crossing from the West Bank into Israel, then back into the West Bank, which is only possible for blue ID holders and holders of foreign passports. The alternative routes proposed by Google Maps also go through Israel. Maps.me takes the longer route which avoids Jerusalem, and can be used by green ID holders (who are generally not allowed to access Israel in their cars, and can only pass through checkpoints if they have an Israeli-issued permit). This issue is illustrated in a video showing an international passport holder (who has no movement restrictions) and a Palestinian green ID holder attempting to reach the same spot. Both Google Maps and Waze use the same platform for reporting errors on maps and/or editing, suggesting edits and adding places to maps. The copyright information on the lower left hand side of Waze’s Help Center is credited to Google. The following table summarizes differences and similarities in the route planning of the three different services. While on some routes, certain apps will direct the driver to routes which are accessible and safe for West Bank Palestinians to travel on, there is no certainty or guarantee with any of the apps that this will be the case. Even when a recommended route is technically available to West Bank Palestinian drivers, they will still have to check this route against current reality and consider it cautiously. This shows that the analyzed mapping apps favour routes that can be used by blue ID holders, even inside the West Bank, contradicting obligations under international law. As seen in the table, Google Maps automatically calculates routes specifically for Israeli ID holders, and marks neither checkpoints nor Israeli settlements.

comparison on route-planning within the occupied Palestinian territories and Israel

Screenshots: Warnings given by the different applications