Terminology and Availability

When the terms ‘West Bank’ and ‘Gaza’ disappeared from Google Maps in late 2016 and were replaced with the general term ‘Israel’, an uproar on social media ensued. The hashtag #PalestineIsHere went viral and reaffirmed the existence of Palestine – a term that had never been used on Google Maps. Google offered an official apology for the deletion of Gaza and West Bank, stating that a bug had caused this (Dent 2016). The hashtag has since been used to advocate the existence of Palestine and its culture, and in early 2018 an online petition to ‘put Palestine on the map’ reached 350,000 signatures (Change.org 2016).

Google Maps labels countries in bold black letters, and ‘undisputed international boundaries’, with solid gray lines (Google Support n.y.). Israel is given a country label and boundary. Jerusalem is clearly marked as the capital of Israel. The demarcation between Israel and the West Bank and Gaza Strip is marked with a dashed line, which for the West Bank is presumably along the Green Line, which Google says indicates ‘treaty and de facto or provisional boundaries’ (Google Support n.y.). The border-marking appears to be the same from both within the Palestinian West Bank and Israel. Google Maps’ different marking of e.g. the Crimea depends on whether the service is accessed from Russia or the Ukraine illustrates how different perspectives can be included in a mapping service.

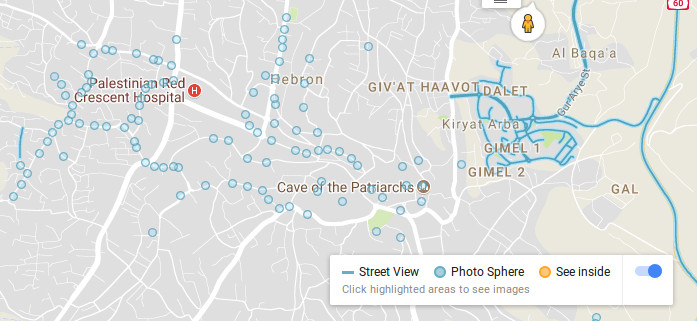

In Google Street View, most of Israel is available to view. However, in Gaza only a few places are marked with photos, as is the case with other Palestinian cities in the West Bank. Within the West Bank, the only places available on Street View are Israeli settlements, with the exception of the Palestinian cities Jericho, Bethlehem and Ramallah. The majority of Route 60 is also available. In Jerusalem, most of the Palestinian neighborhoods are left out, however the Old City, which is located in illegally annexed East Jerusalem, is available (Google Blog 2012).

Palestine was recognized as a ‘non-member observer state’ by the United Nations on 29th November 2012 (UN 2012). Jerusalem was designated international status in UN General Assembly Resolution 181 (II) on 29th November 1947 (UN 1947) and was only recently recognized as the ‘undivided’ capital of Israel by the United States. President Trumps’ decision to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel in December 2017 was strongly condemned by the UN General Assembly (UN 2017) and was opposed by the majority of the UN’s member states.

Through it’s mapping and labelling, one can deduce that Google Maps recognises the existence of Israel, with Jerusalem as its capital, but not Palestine. The West Bank and Gaza do not appear as part of any country or state, as Palestine is not labelled. The terminology used by Google Search was changed in March 2013 from ‘Palestinian territories’ to ‘Palestine’ (MEMRI 2013), although the classification of Palestine doesn’t exist at all in Google Maps.

Screenshot: Marking and terminology of borders and capitals in Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories

Screenshot: Availability of Street View in the Hebron area

Technological Feasibility and Google Maps Alternatives

The Californian NGO The Rebuilding Alliance regularly holds ‘Map-Athons’ where Palestinians and mapping experts add missing Palestinian villages, streets, and residential and agricultural structures to Google Maps. In 2016, The Rebuilding Alliance and Bimkom, another NGO, succeeded in making Google Maps add 236 missing Palestinian villages to their maps (Rebuilding Alliance n.y.). Unlike Google Maps, the Good Shepherd Engineering (GSE) PalMap service provides maps of the West Bank that show both Israeli settlements and Palestinian villages, as well as marking checkpoints, refugee camps, and the separation wall. On their map of historic Palestine, the separation wall is marked in different degrees of completion, with a colour-coded system to mark settlements, Palestinian built-up areas, evacuated Palestinian land, Israeli military bases, as well as the Areas A, B and C and the Green Line. GSE offers a route planning app called iGoPalestine for smartphones, which focuses on guiding Palestinians through the numerous movement restrictions they face. It also offers Street Recordings, similar to Google Street View, for the Palestinian cities Bethlehem, Hebron, Nablus, Ramallah, Jenin and Jericho. GSE depends largely on user subscriptions and fees. Additionally, their ‘Palestine 1948’ initiative allows users to locate information about Palestinian villages and towns that were depopulated or destroyed during the 1948 Nakba (‘catastrophe’, ethnic cleansing and displacement of Palestinians). Similarly, Palestine Open Maps uses historical maps of Palestine to illustrate depopulated villages or areas destroyed from present official maps by combining emerging technologies with immersive storytelling to bring to life stories of Palestinian displacement. These different initiatives, illustrate how the absence of Palestinian villages on Google Maps is not a technological issue, but rather a systematic omission. Despite countless attempts, a Google Maps representative could not be reached to comment on this issue. Although a few Google representatives initially agreed to answer questions about the issue, in the end, none of the persons at Google were actually available to comment.